“There are some words that have been lost from modern usage that I like to bring to my music and have striven all my life to do, beauty, grace, nobility, these are the things that music can bring to us as human beings and I think that it is well that we who make music keep that in our consciousness.”

“There are some words that have been lost from modern usage that I like to bring to my music and have striven all my life to do, beauty, grace, nobility, these are the things that music can bring to us as human beings and I think that it is well that we who make music keep that in our consciousness.”

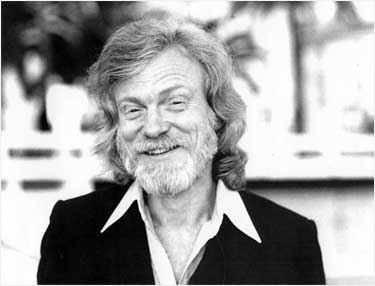

– Gerry Mulligan. An Interview in Verona, Italy – March 26, 1990

“We tend to define people by what they do, and that’s an oversimplification because, how I would define myself is a human being and what I am really concerned with are human values, primarily.”

– Gerry Mulligan. An Interview in Verona, Italy – March 26, 1990

“I somewhere read a long time ago a description by one of the Greek philosophers who said I would like to be in the position of the gods. I would like to be in the position of the gods and sit up on top of a cloud and watch the people, then I would like to change the music of the people and watch the people change accordingly.”

“This in a way has happened because music has become a big industry grinding out product as they call it in great quantities, with no sense of responsibility to the time and place, or the audience that they are playing to.”

“This in a way is I think very important that we understand that freedom without responsibility produces ultimately chaos for the world. In other words, I am my brother’s keeper. I hasten to add that whereas I am my brother’s keeper it is not my place to tell my brother what to do. There is a lot of that going around now.”

– Gerry Mulligan. An Interview in Verona, Italy – March 26, 1990

On Mouthpieces

“My experience with the Martin baritone is very limited, but as I recall from trying them years ago, they are nice horns and play pretty much in tune. One always has to be careful with baritones to take the intonation from the center of the horn, not from the top notes. It’s always a temptation to tune from the top notes because they usually speak so easily. I often find it necessary to have the upper side keys closed a little bit to keep them from going sharp. It feels like you are losing some brilliance of sound to do that, but I prefer having an accurate intonation all over the horn. I also prefer getting an even sound and a matching sound in all registers.

The mouthpiece I use is a hard rubber Gale. It was originally designed for Gregory Rico and are not too easy to find. I’ve always founds the Berg Larsen mouthpieces to be somewhat harsh in tone, especially the metal. This is of course a matter of personal preference and is a question of how responsive any given mouthpiece is to your requirements.

My mouthpiece opening is approximately a five. I say approximately because it had obviously been worked on by somebody before I acquired it. I am very fortunate because whoever worked on it really knew what he was doing. I looked a long time before I found this mouthpiece which suits my needs for most occasions.

My mouthpiece was accidentally damaged recently and I was fortunate that there is a craftsman at Van Doren in Paris who not only was able to repair the damage, but has been able to work up some new mouthpieces based on their mold, that are quite presentable. In the future they hope to duplicate my mouthpiece with the possibility of marketing it under the Van Doren name. I hope that this comes to pass since I get many enquiries from saxophone players about my mouthpiece and since it’s such an obscure manufacturer and so old, I’m not really able to be of much help.

As it happens, the opening of my mouthpiece is very unusual by today’s standards. I see that most manufacturers are putting out mouthpieces with wide-open tips with a relatively short opening for the vamp. My mouthpiece has a very long vamp that opens gradually to the tip, which is not very open at all. I find I can get a more even sound all over the horn by using a less open mouthpiece (especially the tip) and using a stiffer reed. Using a stiffer reed eliminates a lot of the buzz from the sound, which I find very unattractive.”

– Letter to Gerry Buckley. November 15, 1988

In Correspondence with Carlo Peroni

Gerry, I know that you don’t like talking about your past, but please satisfy my whim: in 1947 in New York, at the beginning with Gene Krupa, to which musical style were you close?

“When I wrote for Gene Krupa in 1946, I was very young. What I was trying to do was to combine the elements of the styles that appealed to me: Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie, Lester Young, etc., and the big band idiom. Neal Hefti and Dizzy himself, were the fore-runners of this approach.”

Did you start playing piano or baritone sax?

“I started with a little training (very little!) on piano at age 7, then clarinet at 12, alto sax at 14. I was about 17 when I got my first baritone.”

Nowadays many saxophonists play without piano (you already did that 40 years ago): is this a way to feel more free, that’s to say to concentrate oneself more on the creative side?

“I’m not sure you necessarily feel more free without a piano. In a way it’s more confining because there isn’t the piano to float on. But either way can be just as creative.”

Are you aware that in Italy many schools of jazz players, arrangers and singers are booming? Do you think this music can be taught in a conservatory? If yes, in which way?

“I didn’t know there were many schools to teach jazz in Italy. I should think that this will help those young people gain the technique and introduce them to the realities of playing jazz.

Jazz techniques can be taught, but I think it’s very difficult today to gain the experience needed to become a convincing jazz player – one who can portray and project simple, honest emotions, and can create and help to sustain musical atmospheres. These qualities are quite separate and beyond the mechanics of music. It’s not easy for young players to have the opportunities to play next to experienced older players. The pressure on young players today is to achieve instant success. The record companies at the moment seem only interested in the youngest players – they’ve developed an appetite for prodigies!”

Duke Ellington said that there is no jazz without swing. Some people don’t agree. What is your opinion?

“I agree with Duke Ellington about most everything!”

Excluding jazz, what’s your favourite kind of music?

“19th and 20th century orchestral music.”

By the way, among your records and compositions, which ones do you prefer?

“The Mulligan Meets Webster album; The Age of Steam; Summit with Astor Piazzolla; Lonesome Boulevard, and Walk on the Water.”

It has been almost half a century that I’ve been enjoying listening to jazz. In my opinion nowadays a lot of values connected to this expression of art, such as spontaneity, creativity and excitement, are gradually losing ground. What do you think about it?

“We have to accept and expect that attitudes and values will change and reflect the changing values in the world around us. This has become a more and more materialistic time and we can only hope that there will be a renaissance of idealism and that this renaissance will lead to cultural wisdom and the survival, maybe even the triumph of the higher human values.”

Which are your today’s project, intentions? What do you intend to create in the near future?

“I’m writing new music (as always), my quartet is booked for two concert tours this spring and summer, probably Brazil in the fall, plus three recording projects underway.”

You’ve got an Italian wife and a flat in the centre of Milan. What’s your impression of its environment in general, and more specifically, talking about music, do you consider that it is possible to cooperate together with other Italian jazz players?

“As you know, I like Italy very much, and I enjoy spending time in Milan. Over the years I’ve played with a number of your finest players, including Gianni Basso, Tullio De Piscopo, and Mario Rusca. In fact, the album with Astor Piazzolla was recorded in Milan. It’s a great environment for me; I’m usually able to write very well there.”

– Gerry Mulligan. March 18, 1993

Notes on Miles’s Capital Band

“I was lucky to be in the right place at the right time to be part of Miles’ Band. I’d been on the road a couple of years with various bands by that time, but with Gil’s encouragement, I decided to stay in New York. With all the great bands that were around then, big and little, it was an exciting time musically and everyone seemed to gravitate to Gil’s place. Everybody influenced everybody and Bird was influencer No. 1 on us all.

Gil lived in a room in a basement on West 55th Street near 5th Avenue. Actually it was behind a Chinese Laundry and had all the pipes for the building as well as a sink, a bed, a piano, a hotplate, and no heat. Some of the more or less regulars at Gil’s that I remember are:

John Carisi; almost as hotheaded in an argument (discussion) as I am. Anyone who writes a piece like “Israel” can’t be all bad, right?

John Lewis; our resident classicist.

George Russell; our resident innovator. Wrote a couple of fine, interesting charts for Claude’s band that I suppose there’s no trace of now.

John Benson Brookes; our dreamer of impossible dreams.

Dave Lambert; our itinerant practical Yankee.

Billy Exiner; drummer with Thornhill and our home philosopher with his beautiful attitude toward life and music.

Joe Shulman (Bassist with Thornhill); he believed Count Basie had the only rhythm section.

Barry Galbraith; the Freddy Greene of the Thornhill rhythm section and an altogether beautiful musician.

Specs Goldberg; blithe spirit. A fantastic, intuitive musician who had a tough time trying to channel his freewheeling imagination.

Sylvia Goldberg (no relation); piano student and whirlwind.

Blossom Dearie; Blossom is Blossom.

And Miles; the Bandleader. He took the initiative and put the theories to work. He called the rehearsals, hired the halls, called the players, and generally cracked the whip.

Max Roach; genius. I can’t say enough about his playing with the band. His melodic approach to my charts was a revelation to me. He was fantastic and for me was the perfect drummer for the band. No small statement in view of the fact that Miles brought in Art Blakey and Kenny Clarke on the later dates.

Lee Konitz; genius. Lee had joined Claude’s band in Chicago and knocked us all out (including Bird) with his originality.

For the rest of the band, J.J. and Kai alternated on Trombone. It wasn’t too easy to find French Horn players who were trying to play jazz phraseology, but among those at our rehearsals were Sandy Sigelstein from Thornhill, Junior Collins who could play some good blues, probably Jim Buffington, and Bill Barber on Tuba. He used to transcribe Lester Young’s Tenor choruses and play them on Tuba. What a great player.

As I recall, Gil and I also wanted Danny Polo on Clarinet but he was out with Claude’s band all the time and there was nobody to take his place. Not long before Danny died we had some jam sessions at which he played the best modern clarinet jazz I’ve ever heard.

As I said at the beginning, I consider myself fortunate to be there and I thank whatever lucky stars responsible for placing me there. There’s a kind of perfection about those recordings and I’m pleased that all the material is finally being released in one set. And without phony electronic stereo.”

– Gerry Mulligan. May 1971

Mankind is Perfectable

A Poem by Giulia Niccolai

Insinuating, pervasive,

he entwines, whirls around

and enchants. You begin to follow,

you pursue that flexuous thread of sound

and when you feel it is there, and you know

what it’s saying, and that’s right …

NO, you got it wrong, he runs away

Because he knows that he’s got you,

he’s playing cat and mouse, he changes

into a sharp and fast arrow, into

a cry of pain, and again everything

changes before your eyes, now he is

a powerful and majestic dragon,

the wild trumpeting of an elephant,

he is singing the mad joy, the exaltation

of being able to say all, shape all, evoke

all, blowing magic air through his

glittering, metallic trunk.

A Letter From Gerry to an Airline

Dear Senior Stewardess,

I’m writing to you the same thoughts that I have often written to airlines in the past, and will again as necessary.

I am paying for transportation, not entertainment. When I want entertainment I prefer to choose what and when for myself.

I am a professional musician and the time I spend on planes is put to the best use by writing music, and I spend considerable time on planes every year.

We are a captive audience on an airplane and the assumption that we should all like to hear the same music at the same time, when we are, in fact, on our separate journeys for our separate reasons, is obviously fraught with exceptions. And if one person does not want to hear any canned music, then it is the company’s responsibility to turn it off. I don’t buy airline tickets to be upset by unwanted “entertainment”.

Remember, we are buying transportation not entertainment.